Stafford asylum officially opened on 1 Oct 1818. The first months saw patients arriving from other institutions, including private madhouses and workhouses, as well as individuals who had not yet been hospitalised, some of whom may well have been cared for at home for some time. By December there were 57 patients in the asylum, both private patients and those classed as paupers.

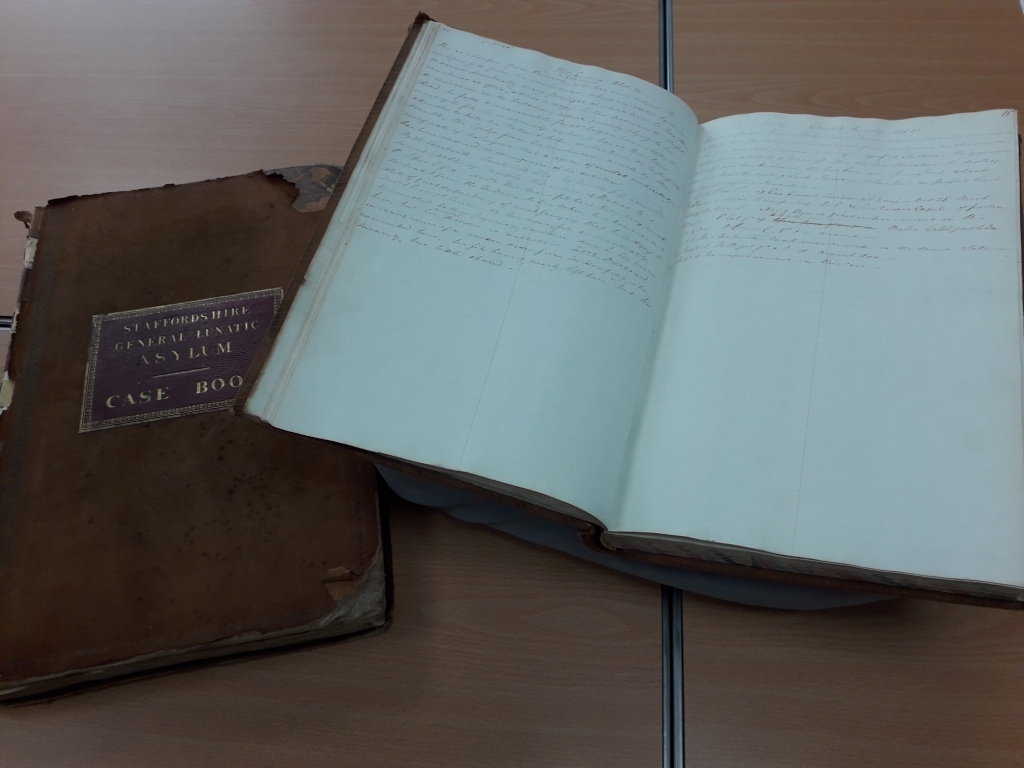

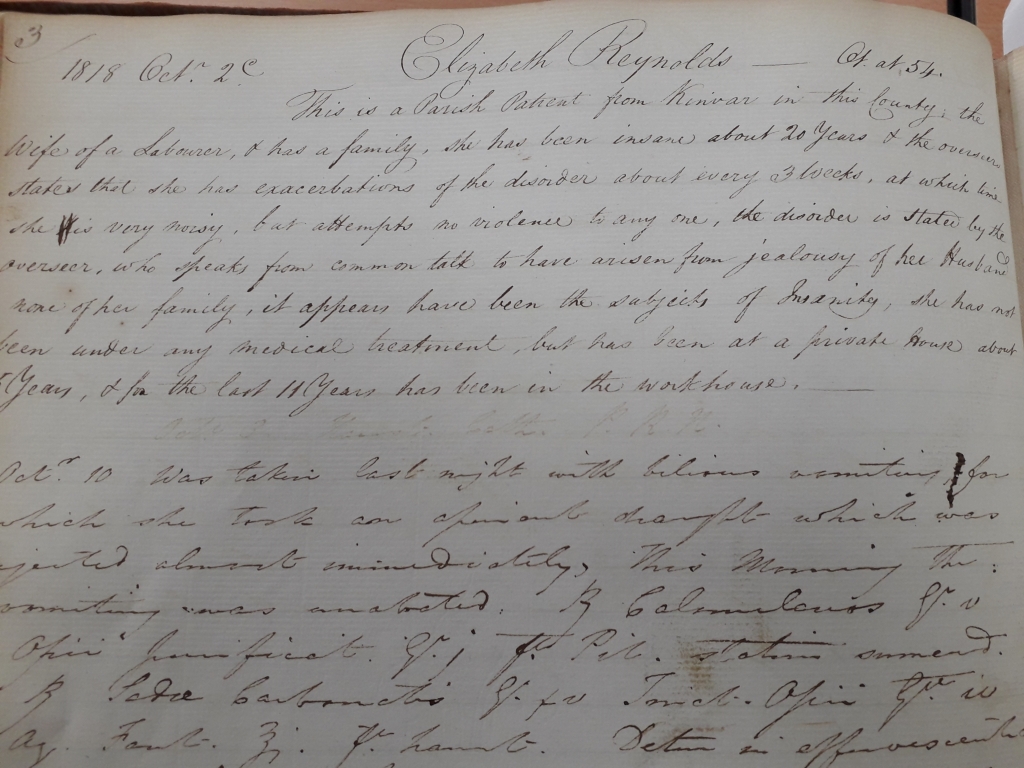

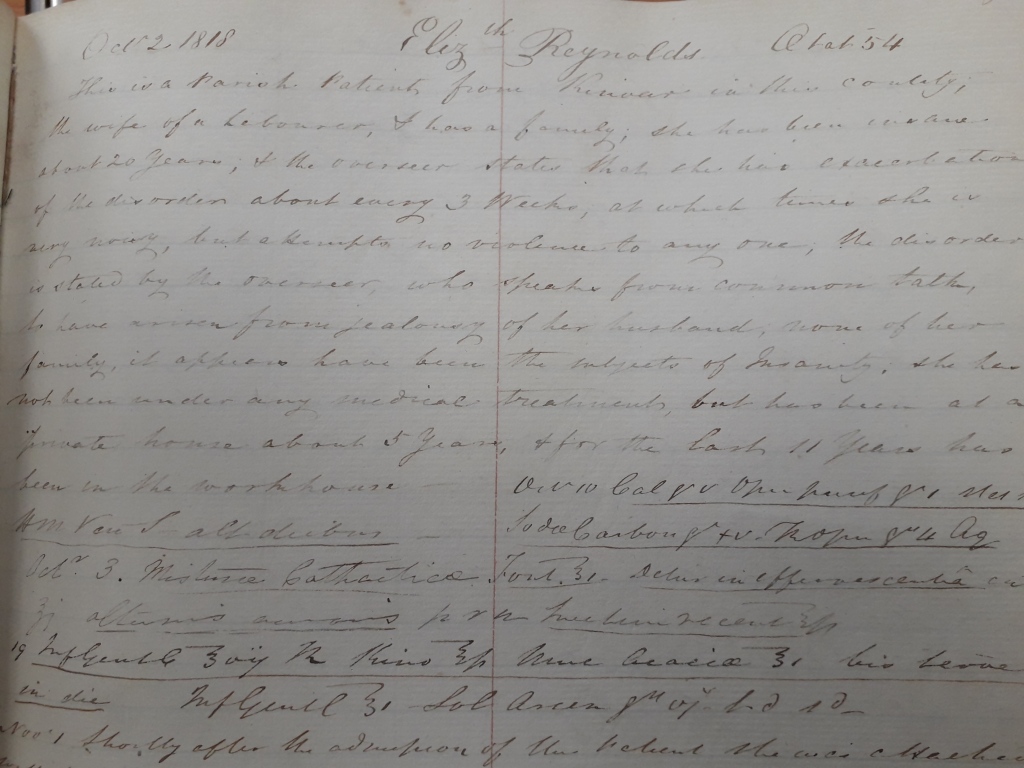

The earliest record from our three County asylums is the first Stafford Casebook 1818-1827, and the accompanying Apothecaries Day Book from 1818-19. What are these documents, and how can we interpret them?

On arriving at the asylum, the mental and physical state of the patient would be recorded in the casebook, and then a log kept of their symptoms and progress. Later casebooks are more clearly structured, with the same information entered for each patient. They are usually accompanied by admission registers, with the information taken down on the first day of admission (name, date, chargeable union, date of certification and name of doctor etc.). For this early period, however, admission registers do not exist.

What we do have to accompany the early casebook is an ‘apothecaries day book’, which details more of the patients’ symptoms and the treatments and drugs prescribed. This document only runs from 1818-19, but it is helpful in supplementing what the casebook tells us. Together, these two documents give us a picture of what symptoms were recorded, and what treatment was attempted.

A complication in making use of the 1818 casebook is the way it was kept – male patients at one end of the ledger, and female patients at the other end, so that we can only place patients in admission order by referring continually to both sections.

What information does the casebook give us? For this first casebook, the type of information about each patient varies, as it is completely free text in nature. One example of an early patient is not untypical. Charity Rowley was admitted on 17 Oct 1818, just over two weeks into the life of the asylum. In Charity’s case the following was recorded – she was 51, married, and of pauper status. She had 13 children, the youngest being 10, was from Stoke, and had previously been in Thomas Bakewell’s Spring Vale asylum (from which several patients were transferred) for 7 months ending in Jan 1818. She had been ill for two years and had had no real lucid interludes during that time.

In many cases the symptoms and also delusions of the patients are recorded – in Charity’s case, she had threatened to destroy herself and her husband, and her illness was believed to stem from religious fervour. She was finally discharged in Nov 1830 as harmless and incurable.

Some patients have more detailed notes, and some we know little about from these records. Treatments are not entered for every patient, but the day book gives us an idea of the range of treatments which the Superintendent authorised. Treatments, when they are recorded, fall into several basic types. Electrification is fairly commonly recorded. This would entail the use of magnets or static electricity, and only later developed into electro-convulsive therapy.

The casebook records early patient Joseph Hunt, a 28 year old forgeman from Rugeley whose insanity was believed to have been brought on by drink, as ‘electrified’ three times to no effect. Charity Rowley was electrified on 31 Mar 1819, but the effects of this were not stated. Other methods recorded in the casebook included ‘the swing’, an invention of Erasmus Darwin, whereby a patient would be rotated in a chair suspended between ceiling and floor. Miss Woolrich was placed in the swing in 1820, and, not surprisingly, was recorded as less violent after the treatment due to her ‘vomiting completely’.

Restraint, isolation, hot and cold shower baths and blistering were also commonly recorded. Drugs were few, and their effects were far from understood. The most common was digitalis, which is still used to treat heart disease. Others included mercury, cannabis, opium and purgatives. Humeral theory, at the time diminishing as a central medical tenet, still informed approaches to insanity, and so changing the balance of the body’s humors, through purgatives, bleeding and also dietary intake was still one framework within which patients’ symptoms were understood.

Diet was perhaps the most commonly prescribed treatment, and this was tried on all classes of patients. A generous diet was often seen as a necessary step to recovery, even more so where a patient was admitted in a poor physical state. Even patients with better health were still prescribed items such as coffee and cream, and most usually ‘generous diet’. Alcohol was also useful in pacifying patients, as well as being seen as a medicine in its own right. Pints of ale, multiple times a day, were often prescribed. Maria Lewis, a 46 year old wife of a tradesman from Wolverhampton was prescribed meat twice a day and a pint of ale twice a day to help ease her hysteria brought on by a traumatic miscarriage. A Mr Redfern was given 2 glasses of wine a day, and was also bled with leeches – neither of which could help to prevent his death.

The early casebook gives us a snapshot, albeit a partial and often confusing one, of the ways in which symptoms were understood by the hospital’s medics. It shows us what they believed to be significant enough to record, and how treatment was attempted using very limited knowledge and assumptions about mental health. We will look more closely at some early cases next month, when we will concentrate on the patient experience from the early days of Stafford through to later decades.