By Rebecca Wynter

Fires always change things. From Grenfell Tower to the Australian Bushfires, they enable us to see clearly the failures of design and human behaviour. What seems obvious in the aftermath is the terrible inevitability of the impact of lack of investment or attention. This has always been the case, even if the way we have understood ‘accidents’, like fires and burns, and apportioned blame has changed over time.

By the start of the nineteenth century, the idea that unintended injuries and deaths could be providential or an ‘Act of God’ had largely been eclipsed. With growing confidence and understanding of the body, as well as the development of new technologies, alongside fire insurance and actuarial science, events came to be considered as more predictable; risks could be managed.

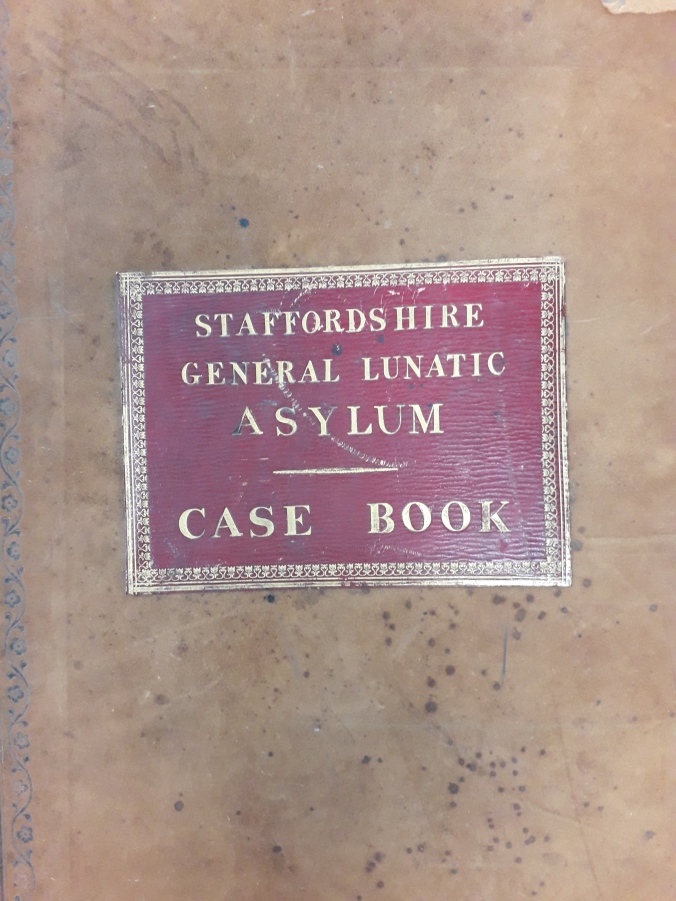

Care was at the heart of the new, modern asylums, like Stafford, which had opened in 1818. Yet people who were admitted were there because someone had considered them a risk to themselves or to others or, indeed, that the community posed a risk to them.

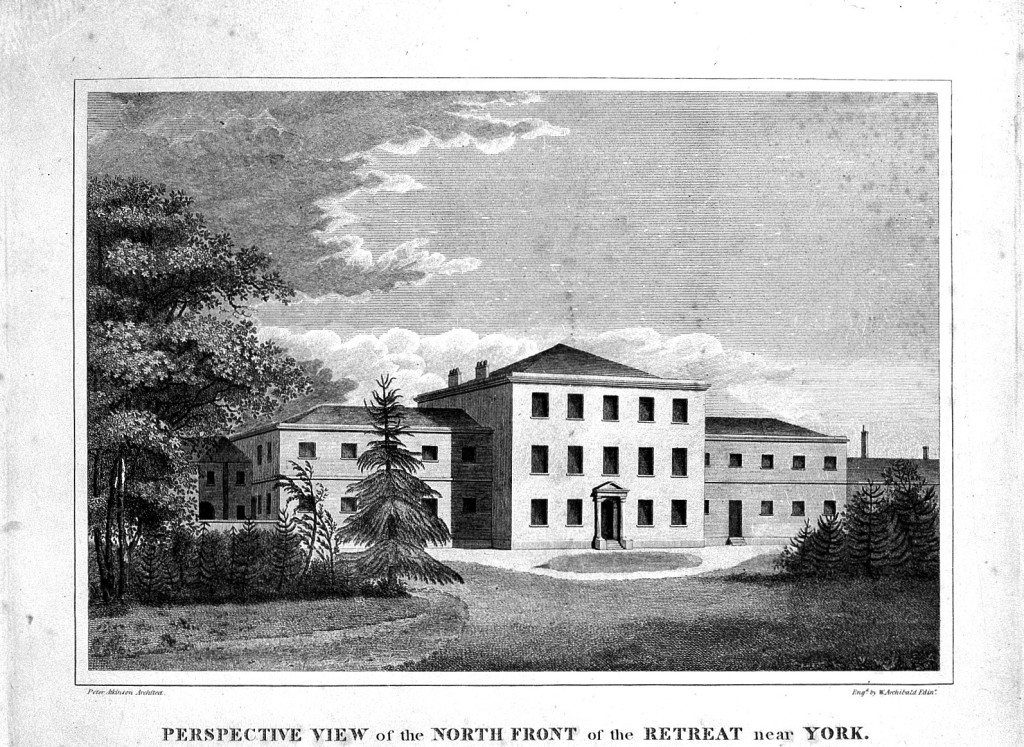

The ideas around fires were, however, less developed. Fires were clearly understood to be hazardous for buildings. A previous blog post discussed late-nineteenth-century efforts to keep asylums safe from flame. In fact, efforts had been embedded since the modern facilities had come into being. At the famous progenitor of UK facilities, The Retreat at York, opened in 1796 by the Quaker Tuke family, for example, fire-safety measures had been built into the site. In Samuel Tuke’s Practical Hints on the Construction and Economy of Pauper Lunatic Asylums (1815), he directed that ‘[a]ll the partitions as well as the outer walls’ were to be of brick. This new type of purpose-built institution imported industrial design and gradually began to integrate vaulted ceilings, iron struts and structures, and fire-proof floors, all employed in order to avoid flammable wood.

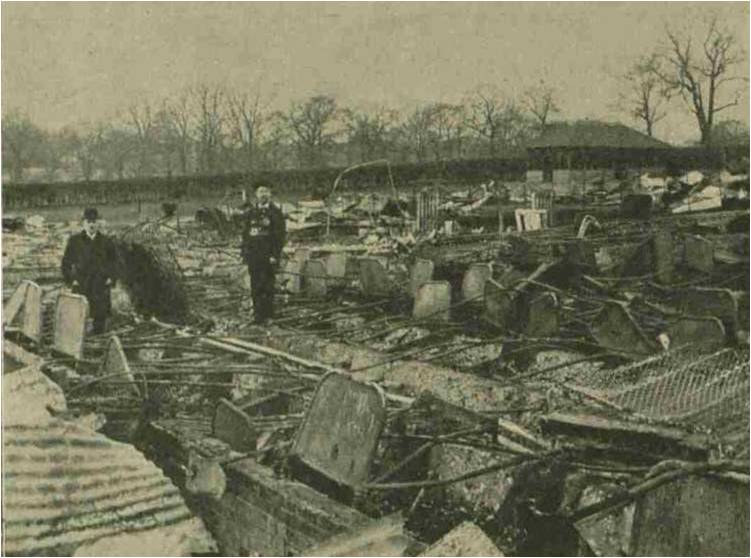

That fires could be designed out of buildings is evidence that there was an understanding of risk developing, but it seems that more often it was as a result of clarity after the fact. Gloucester Asylum’s new fire-proof floor, for example, was only erected in 1833/4, after a devastating inferno had destroyed much of the inside of the building. The banning of temporary wooden structures at these facilities only happened after an annexe adjacent to Colney Hatch Asylum’s main building caught light in London, 1903, and its design, cladding and combustible materials ensured a blaze so ferocious that 51 women died.

This short-sightedness—for, in Colney’s case, temporary structures could have been built with safe cladding, and for a similar cost—extended to more intimate incidents of fire, such as the one at Stafford Asylum in 1821. These sorts of events were rare inside asylums in comparison to those which took place in the home (and often to children), but like the outside world, it was frequently women who suffered due to their long skirts and dresses.

‘Women wearing crinolines which are set on fire by flames from a domestic fireplace. Coloured lithograph, ca. 1860’ (Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mrs Ann Clemson, so titled due to her belonging to the body of ‘Second Class’ patients – people, often of the ‘middling sort’, who paid for their care, but were subsidised by the charitable coffers of Staffordshire General Asylum – was admitted to the institution on 21 March 1821. In her case notes, Superintendent John Garrett took care to note that at 38-years-old Ann had only been ill since lying in, around five months previously. She described a lightness and swimming in her head, and feared for her salvation. She was aware of her ‘erroneous’ ideas, but was also suicidal. With this history, Garrett would have known that Ann, whilst mentally disordered, belonged to a group of patients that usually recovered and continued perfectly well thereafter. Unless, that is, she had another child, meaning she might experience ‘puerperal insanity’, an ancestor of what is now termed ‘postpartum psychosis’.

Three days after her admission, her case notes recorded that Ann ‘set fire to her clothes, from the imagination that as her children were burning, she might as well burn too; the burns are very extreme and severe, and there is no probability of recovery from them’.

The official that visited the asylum to monitor its running wrote in his obligatory report in the Visiting Magistrates’ Minutes that Mrs Clemson had befallen ‘a dreadful accident’. It appeared:

‘she was left in a room with two other patients, and having exhibited no symptoms or any intention to destroy herself, but on the contrary being remarkably cheerful and sensible, it was considered perfectly safe to leave her with them, the patients themselves being considered in some measure a security against such an accident … no blame seems to attach to anyone, but I consider it would be prudent to have fixed fireguards in all the rooms appropriated in the use of patients, whatever class or description such patients may be of.’

Even from these two pieces of evidence—the case notes saying that she wanted to kill herself, the Visiting Magistrates’ Minutes saying she had shown no inkling of suicide—it is clear that something was awry in the explanations employed to excuse staff. (Although it is entirely understandable that unplanned and momentary lapses in attention could have happened: they happen to us all.) Less than two months before Ann died, another second-class patient had killed himself. The Visiting Magistrates noted that ‘no blame can attach to any officer of the Establishment’, but they also ‘thought it right to recommend increased caution and vigilance to all the Keepers’ (the forerunners of mental health nurses).

However, the framing of Ann Clemson’s incident demonstrates the fundamental disconnect in thinking between risk and blame. To be sure, the incident was not seen as an Act of God, but neither was it expressly described as the fault of the weak safety mechanisms in place. In fact, and whilst patients are framed as culpable in the two accounts—the first, Mrs Clemson herself, and the second, the two patients left with her as security—the event was considered an accident, even if it is apparent that the cause was systemic and collective failure of a raft of different people, from the architect to the magistracy to the asylum authorities and staff at all levels.

But in its aftermath, what connects those in the past with you reading this blog post is the inevitability that these circumstances would harm someone. Whether we can design systems that recognise the humanness of mistakes in attention whilst also ensuring the ease of freedom remains to be seen, but we should by now have internalised the need for careful investment in health and safety so as to avoid injury. Something as simple as a fixed fireguard would have saved Ann—and who knows what difference she would have made to the world and to her children?

Primary sources:

Staffordshire County Record Office, Staffordshire Asylum: House Committee Minute Book (volume 2), D550/3.

Staffordshire County Record Office, Staffordshire Asylum: Male and Female Case Book, 1818-1827, D4585/6.

Dr Rebecca Wynter is a historian of medicine and Quakers at the University of Birmingham, and is a member of our ‘Staffordshire Asylums’ Advisory Board. This blog post has drawn on her PhD research on Stafford Asylum and Prison, but is also thanks to her work on the AHRC-funded project, ‘Forged by Fire: Burns Injury and Identity, c.1800-2000’. You can read more about the project here.

Interesting piece. Thank you…

LikeLike